Failing and Succeeding: Analysis of the St. Louis Food Ecosystem

Introduction

Food City set out to learn how people accessed food in an attempt to understand the impact of geography, poverty, and race on food availability. Throughout 2023, the Food City team administered surveys at community events and through semi-random sampling in the St. Louis metropolitan area. Questions are primarily geared toward understanding the availability of food choices and the effect that socioeconomic status has on shaping individual decision making. What challenges do people in the St. Louis area face? Are those challenges equally distributed across race, income, and gender?

Executive Summary

The Food City survey analysis report highlights the findings from a survey of the St. Louis food ecosystem. Food City administered the survey with the goal of understanding the status of households involved in the production and consumption of food in the St. Louis metropolitan area. For example, how does income affect food security? How does geography shape the choices households are able to make? Where and how is the food ecosystem of St. Louis failing to provide nutritious options for its people?

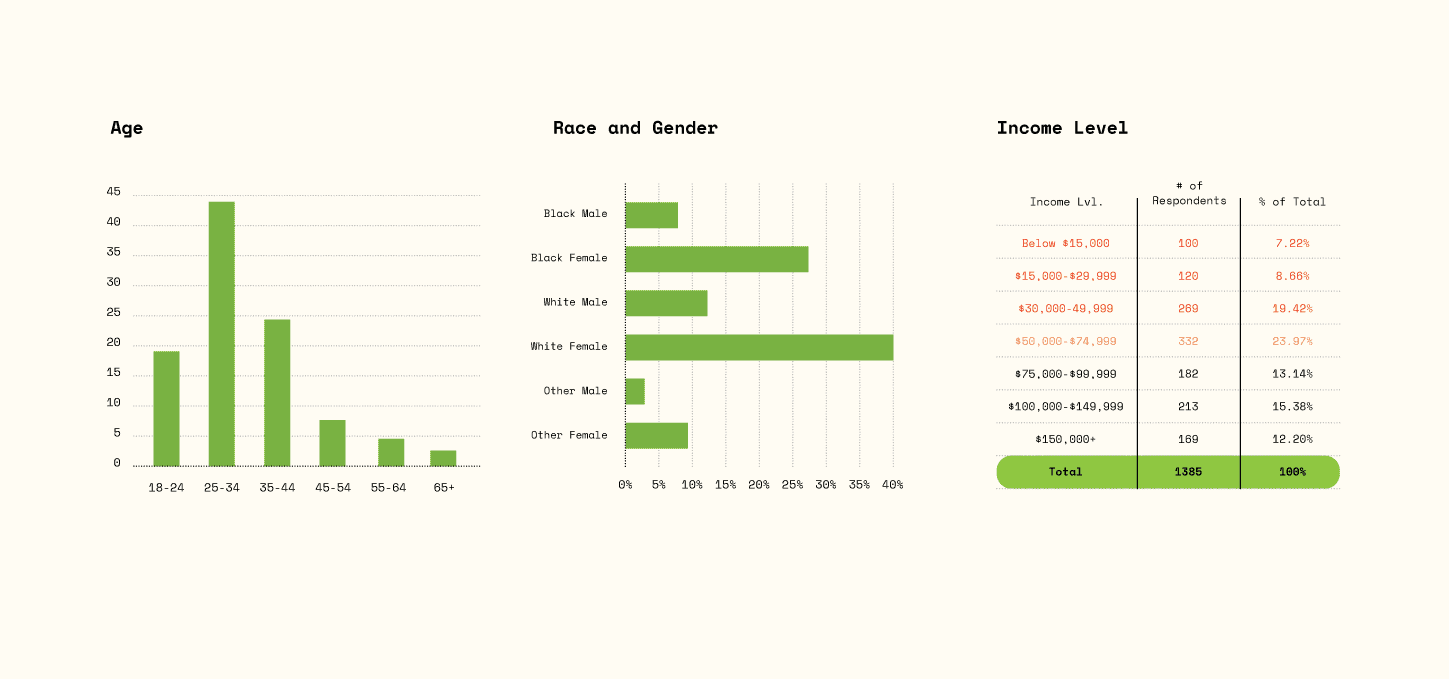

Overall, the survey reveals significant differences among income groups, with additional differences associated with race, and the role that gender plays in the provision and gathering of food. In a survey primarily administered at different events focused on food, females comprise a disproportionate share of the respondents. This highlights the ways in which gender norms persist, with females more than twice as likely to respond to the survey.

While females were overrepresented among our respondents, the survey captured a fairly representative sample across both income and ethnicity. Respondents’ income levels reflect reported data from the last census, as do our respondents’ ethnicities.

In addition to income, other factors also appear to impact food security. Reliable transportation is a much bigger challenge for those who struggle the most with food insecurity. Geography represents a place-based struggle for many of our neighborhoods and communities, with respondents indicating they face a tradeoff between healthy foods and convenience.

Our analysis provides insights into these and other challenges faced by the St. Louis metropolitan community. Below, we discuss the survey itself, the relationship between the sample and the population, and the inferences we are able to draw from the data. We conclude by highlighting what respondents indicated is missing from their neighborhoods, and show how community partners are starting to fill those gaps.

Survey Respondents

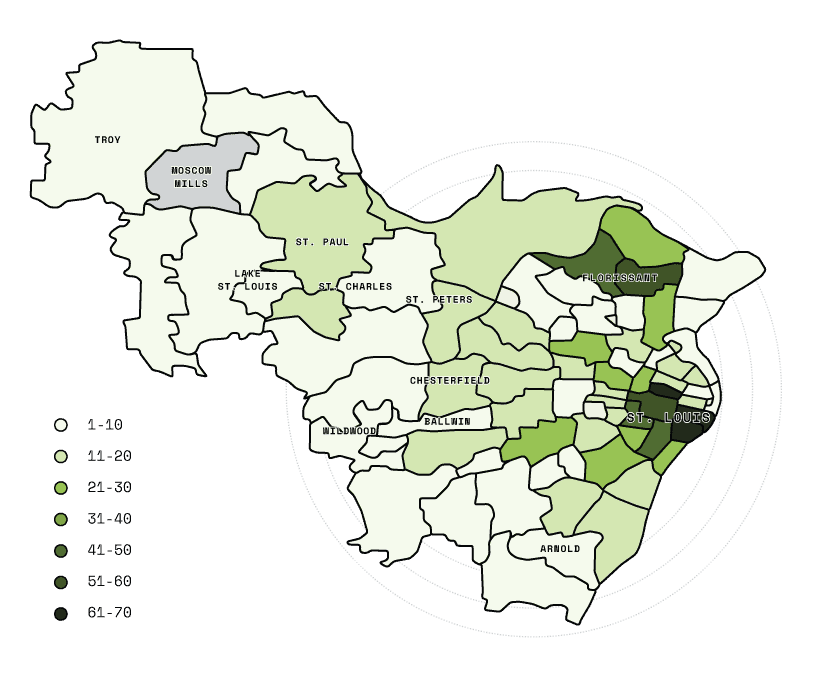

The surveys were administered between August and December of 2023, and the plurality of our respondents came from St. Louis City and County, with some additional respondents coming from St. Charles County and Lincoln County.

Number of Respondents by Zip Code

Respondent Demographics

Age

The median age for residents of St. Louis is 36.8 years. The median age in Missouri is 39.1 years. The median age for survey respondents is 32 years, so the respondents are a bit younger than the population as a whole.

Race and Gender

Missouri and St. Louis populations are 51% female. Respondents to this survey are 73% female. So, women are overrepresented in this sample. This makes sense as women are often still tasked with unpaid household labor such as securing food and caregiving, even if they are working full time. Broken down by gender and race, the most common respondents were white females (40%) and Black females (27%), followed by white males (13%) and other (non-white/non-Hispanic/non-Black)

females (9%).

Income Level

The median household income in Missouri is $64,811. The federal poverty threshold for a family of four is $31,200. Nearly 16% of respondents report a household income below that level. An additional 20% reported income just above that level, in the $30,000-$49,999 range. The most common income range for respondents is those earning between $50,000-$74,999, with nearly 24% of respondents identifying with that income level. For our remaining data analysis, we have consolidated the income ranges to reflect households that may be living in poverty (below $30,000), households that may be impoverished ($30,000-$49,000), households that are living near the median household income (between $50,000-$74,999), those above the median income ($75,000-$100,000), and those making more than $100,000.

Survey Administration

The survey was administered to individuals who hold a variety of roles in regard to the local food ecosystem. Consumers/citizens made up the vast majority of respondents, at 70%. Business owners and entrepreneurs comprise 15% of respondents, while 5% are industry professionals, 2.3% are organizers/activists, 1.1% are policymakers, and 5.9% had another role.

The data collected in the survey did not include the race of the respondents, so we employed a widely used method in social science research to predict their race: extrapolation from the geographic distribution of names and ethnoracial groups in the U.S. Census (Grumbach & Sahn 2019). Using this approach, we identified that 53% of respondents are white, 35% are Black, and 12% are in a combined “other” race/ethnicity category. This broadly falls in line with the proportion of respondents identifying as each ethnicity in the latest census data for the City of St. Louis and St. Louis County (29% Black or African descent for the city and county combined, and 59% white non-Hispanic). One significant drawback to this method is the erasure of other or multiracial individuals — the latter of which is especially common in social science research and policy development. We think, however, that being able to talk about the intersection of race and income on food security is beneficial, and future work should incorporate questions on race and ethnicity to better understand intersectionality and the inclusiveness of the food community in the St. Louis metro area in general.

Food Choices and Availability

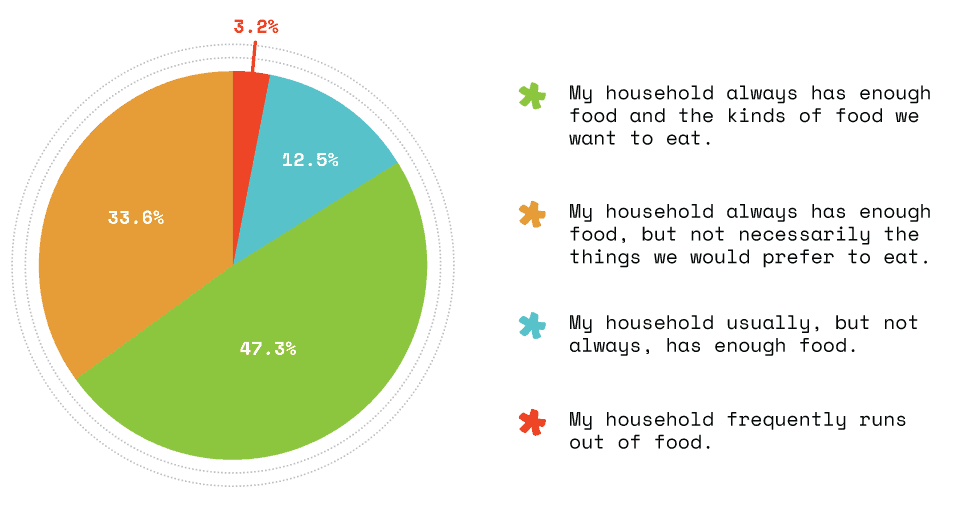

When asked which statement was most accurate about their household food choices, a plurality of respondents said their household has enough food and the kinds of food they want to eat. However, for over half of the respondents that was not the case. While it might seem reassuring that only 3.2% of households said they frequently run out of food, when we consider the effects of income on these responses, we find significant disparities. For households with income below $15,000, 7.5% of respondents indicated that they frequently run out of food.

The percentages are similar for households with income of $15,000-$29,999 (6.1%) and $30,000-$49,999 (6.3%). Overall, households at or below the poverty line were more than twice as likely as other respondents to say they frequently ran out of food. For households with incomes of $50,000-$74,999, we see a decline to 2.8%, and for those making $75,000 or above, the figure is below 1%.

a plurality of respondents said their household has enough food and the kinds of food they want to eat. However, for over half of the respondents that was not the case.

Income and Food Accessibility

Respondents were asked to select a statement that describes whether they have enough food and the kinds of food they want to eat. When examining the optimal response — that the household always has enough food and the kinds of food they want to eat — households with lower incomes were much less likely to indicate that this is the case for them. Only 23.6% of households with incomes below $30,000 and 24.3% of households with incomes between $30,000-$49,999 said they always have enough food and the kinds of food they want to eat. Higher income households were much more likely to say this is the case, with 45.7% of households with incomes between $50,000-$74,999, 53.5% of households with incomes between $75,000-$99,999, and 74% of households with incomes above $100,000 saying they have enough food and the kinds of food they want to eat. Again, households near or below the poverty line were almost half as likely to report having enough food and the kind of food they want to eat. Over and over, respondents indicated that income impacted their food choices. One quote which typified the responses was “I feel like we have no choice but to accept certain foods due to low income, it is more expensive to eat healthier.” Another individual said, “It is much more difficult to eat healthy/nutritious on a limited income. This takes a toll on people physically and mentally.”

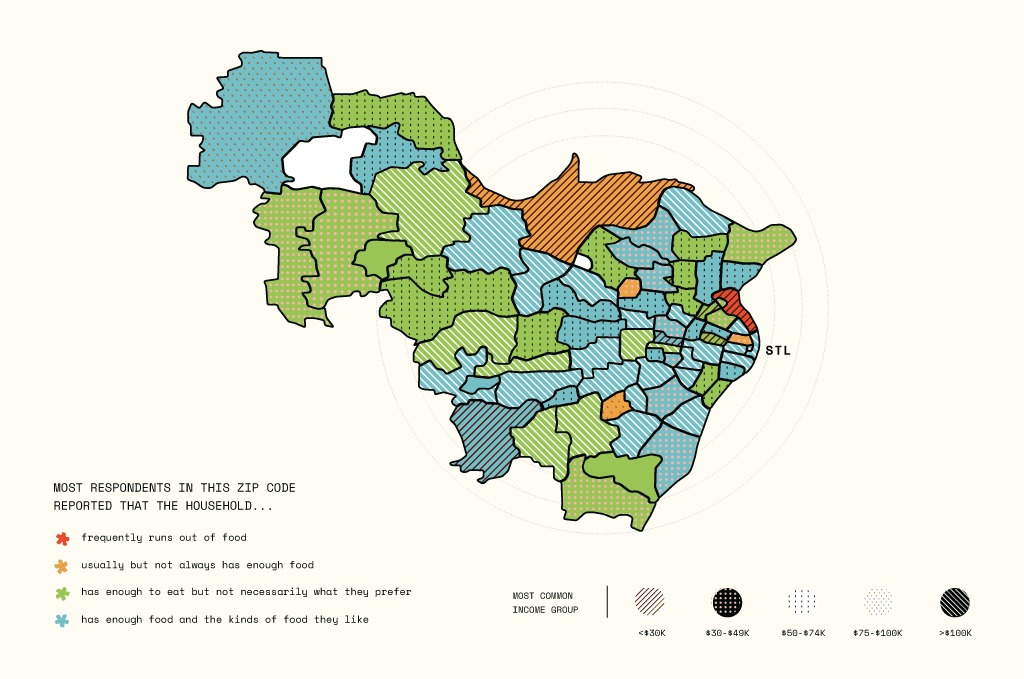

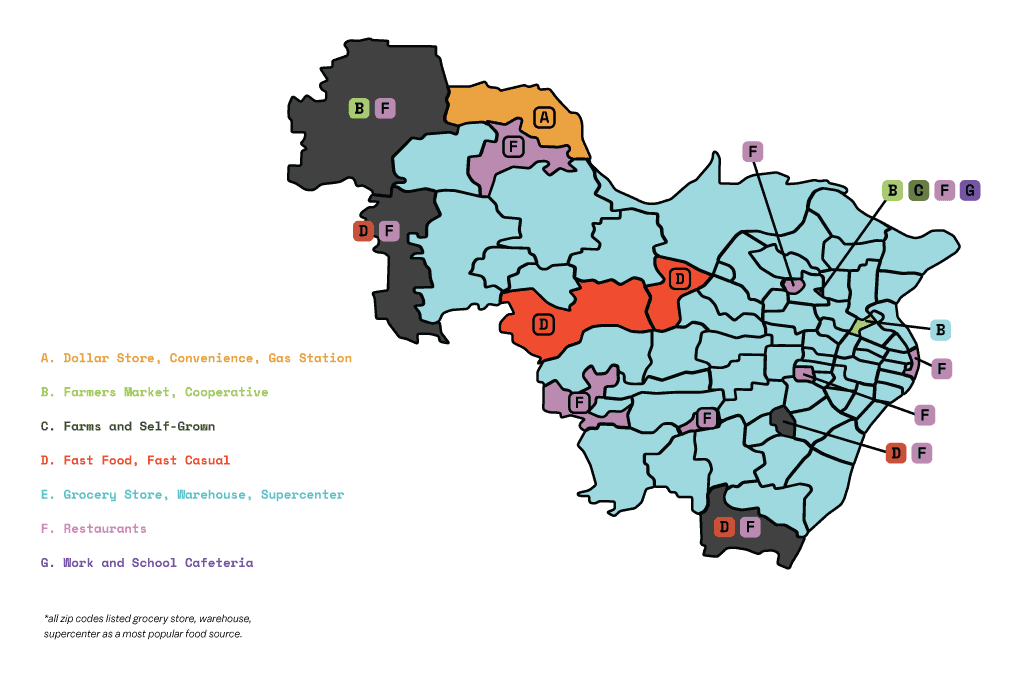

The maps demonstrate the geographic distribution of these kinds of responses by zip code. North St. Louis City suffers the most from food insecurity, with a clear association between the average income and the accessibility of good food. Respondents’ indications that their income levels are lower in North St. Louis City aligns with census data that demonstrate lower household income levels for that region. Respondents in St. Charles County also had lower income levels and not always enough food. This trend does not align with general income levels in St. Charles County, where household income is higher than Missouri’s median. However, it tells the story of the survey respondents who live in that region. The I-40 corridor is one of the wealthier areas of the region, and the map below demonstrates that respondents living in that area have higher income levels and are more likely to say that they always have enough food to eat and have the kinds of food they like to eat.

A common response that is geographically spread throughout the region is that their household has enough to eat, but not necessarily what they prefer to eat, as indicated by the areas in green on the map.

What’s Missing From Your Neighborhood or Community?

Analysis of Options

This map shows the most popular food sources by zip code in the St. Louis region. Overall, grocery stores (including big box warehouses and supercenters) was the most common response, as one of the most popular choices in nearly all surveyed regions. Fast food and fast casual restaurants, as well as sit-down restaurants, were also frequently selected. Less popular across zip codes were work and school cafeterias and farmers’ markets and food cooperatives. Food pantries and programs like Meals on Wheels were very rarely selected.

Regional Economic Development

Roughly a third of respondents, and over half of those who answered the question, indicated that they would eat differently if money were not a factor. Common themes in the open-ended responses included buying more from locally owned grocery stores, eating healthier, and being more likely to cook at home rather than eat for convenience. Geographic access to locally owned grocery stores was also highlighted. Respondents indicated that they felt local grocery stores were more expensive and often inconveniently located, thus it was more cost effective and easier to shop in larger chains and big box stores. If more locally owned grocery stores were present in the community, respondents indicated they would be more likely to shop there. One respondent indicated that they “had to drive further for healthy options,” while another said they “sacrifice other personal things to make sure good food is in the budget,” adding, “I drive long distances to grocery shop.” Perhaps the most common response pertains to how income impacts respondents’ ability to purchase healthy foods. One respondent said, “100% we would eat differently. While we make decent money, we still have bills to pay and can’t devote all of our money to buying healthy and nutritious foods. If it wasn’t a factor, I would try and eat all natural and organic from locally sourced markets and farms (local butchers, etc.).” This was a typical response, highlighting that even those who feel their income is decent still struggle to access and afford healthy and nutritious foods. Another respondent said, “If money was no object, I would be able to provide the healthy and natural foods needed.” Cooking more at home or eating more nutritiously when going out was another recurring theme in the responses. One respondent indicated that they would cook more healthy meals at home with fresh vegetables, and another highlighted how income limits for government programs like food stamps alter healthy behaviors in negative ways, saying “Yes I would be more healthy, probably cook at home a lot more. Just like I did when I was on food stamps, I cooked at home a lot more.”

“…we still have bills to pay and can’t devote all of our money to buying healthy and nutritious foods. If it wasn’t a factor, I would try and eat all natural and organic from locally sourced markets and farms, local butchers, etc…”

- Anonymous Survey Respondent

Designing the Future of Food

When we asked respondents what was missing from their communities, several common themes arose. These include the need for fresher produce through things like community gardens, farmers’ markets, and better grocery stores; better health and nutrition education; and affordable healthy options.

Gardens, primarily community, but also personal, appear to be a major desire within the St. Louis food ecosystem. Respondents frequently mentioned them as something they felt was missing, highlighting how they improve food access, provide healthy options, and develop a sense of shared responsibility and community. One respondent said that community gardens or cooperatives “could provide opportunities for residents to grow their own produce, fostering a stronger sense of local sustainability.” Another indicated that community gardens could be useful to the entire St. Louis metro area. Farmers’ markets were also frequently highlighted as missing, as respondents see them in nearby communities and think having better access to them would improve lives in their community as well. Respondents in Florissant and Carondelet specifically pointed to opportunities in nearby Ferguson and Soulard as something they wish they had. Another respondent said, “Community gardens and farmers’ markets would be beneficial to my neighborhood and others across the metro. These amenities/resources do exist, but not in a way that can serve all consumers, especially low-income communities.”

Finally, a third related theme highlighted by respondents was the lack of education about what nutritious options exist, how affordable they are, and how they can be accessed. Simply put, respondents indicated “food education” over and over again, in a variety of ways; they specifically cited “access to free produce and education on healthy eating,” “community education classes based around nutrition and healthy living,” and “food education and culinary training resources.” Similarly, another respondent, in addition to hoping for healthier grocery stores or community gardens, said “more marketing and advertisement of these opportunities,” adding that “so many St. Louis gems are hidden within neighborhoods and they never grow because people don’t know about them.” Even when opportunities for healthier eating exist, many individuals do not know about them because of a lack of education, marketing, and general awareness.

As one respondent noted in detail, “In my ideal neighborhood, I would love to see a diverse array of food resources and amenities that cater to the diverse tastes and needs of the community. First and foremost, a vibrant farmers’ market would be a cornerstone, providing access to fresh, locally grown produce, artisanal products, and a platform for small-scale food entrepreneurs. It would also be wonderful to have a community garden where residents can grow their own food and connect with neighbors who share a passion for gardening. Additionally, a range of dining options should be available, from family-friendly restaurants to cozy cafes offering international cuisines and healthy, sustainable menu choices. A well-stocked grocery store with organic and locally sourced products would be essential, making it convenient to shop for everyday essentials. Finally, cooking classes and educational programs focusing on nutrition and sustainable cooking practices would empower the community to make healthier and more environmentally conscious food choices. These amenities would not only nourish the body, but also foster a sense of community and promote food sustainability in our neighborhood.”

This survey report has highlighted a number of challenges faced by the St. Louis community. Much of the remainder of the book, written by a diverse set of contributors across the food ecosystem, identifies ways in which individuals and organizations are making progress confronting these challenges.

Data Limitations

We want to acknowledge that the survey suffers from several limitations common in survey research. Most importantly, there is a possibility that answers may be biased due to self-reporting and from the sampling technique. Self-reporting bias might be especially relevant in terms of indicators related to income and hunger, such as over-reporting income or under-reporting lack of nutritious choices. Due to the nature of the sampling technique, it is possible that these respondents are not representative of the St. Louis metropolitan community population. However, given the distribution of incomes across the sample, we think this broadly mirrors the distribution of government statistics.

Finally, there are a number of factors that were not accounted for in the survey — including the explicit question of race and educational attainment. While we were able to employ a method to slightly overcome the lack of self-reported race data, asking a question that specifically encourages respondents to identify which race(s) they identify with would allow a better understanding of the intersection of race, sex, and income on the food ecosystem in St. Louis. Aggregation to the zip code level may additionally obscure some geographic factors that could be better understood at the neighborhood or census tract level, which could provide more nuance.