Saint Louis Food System, Part 1 : Everybody Eats

Introduction

Years before President Barack Obama was elected, I settled on a theory: The majority of African Americans would remain victims of generational ills until they controlled the economic and social outcomes of their communities.

OK, it wasn’t a unique hypothesis. Long before I was born, other Black revolutionary leaders preached the gospel of do-for-self economics. Similarly, I concluded that unless Black people controlled the money flow, and controlled opportunities to create and generate wealth within their own communities, generational poverty, crime, and hopelessness would be an ongoing reality.

The problem with this theory was I couldn’t think of an easily accessible, controllable mechanism that Black people could command that would generate wealth for themselves or their children in their

own neighborhoods.

Then, in 2010, I read about one of Obama’s initiatives that gave me hope:

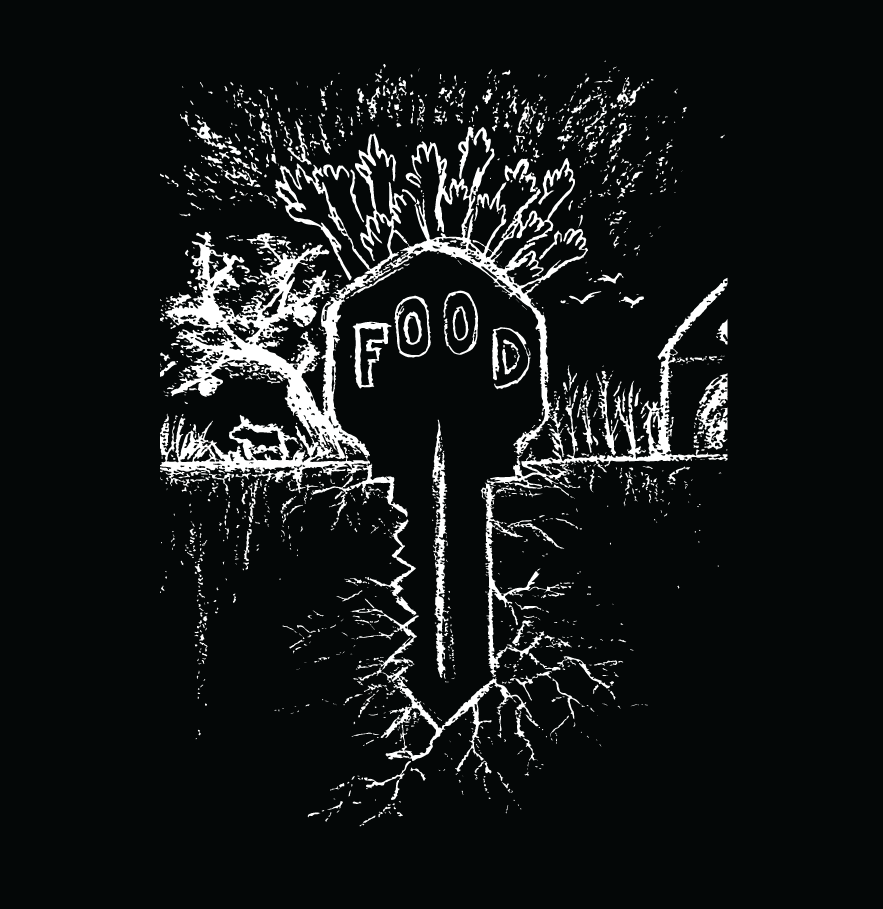

Food.

33%:

The share of the U.S. population that live one to 10 miles from the nearest supermarket, supercenter, or large grocery store, according to USDA data.

Remember, Obama was elected during the worst economic crisis in America since the Great Depression. About two years into his term, his administration announced the $400 million Healthy Food Financing Initiative. The idea was to use federal funds to bring grocery stores and other healthy food retailers to underserved urban and rural communities across America.

Bingo! A viable outlet for my philosophy. There are thousands of food deserts in low-income Black communities nationwide that lack access to healthy food. In my mind, Obama’s food financing initiative seemed like a viable way to rejuvenate long-ignored, long-impoverished Black neighborhoods. After all, everybody eats.

In researching the cities, individuals, and agencies taking advantage of this government initiative, I sadly noted that the majority were white people or white-led nonprofits in urban settings. It blew my mind that none of the most renowned Black organizations or individuals — not the Urban League nor the NAACP, not Jesse Jackson, Louis Farrakhan or Al Sharpton, no high-profile Black agency or personality — were promoting the idea that we could use government resources to create food-based economic engines in Black neighborhoods.

So, I decided to try. In 2012, buoyed by my knowledge of Black pioneers, I embarked on a bodacious (and, in retrospect, naive) attempt to create a nonprofit aimed at teaching urban kids entrepreneurism through food. I called it the Sweet Potato Project.

Luckily, I secured a partnership with Steve Jenkins, director of food innovation and entrepreneurship at Saint Louis University, who jumped on board and graciously gave my students access to his expertise and the university’s industrial kitchen.

The basic idea was to pay youth ages 16 to 20 a minimum wage during the summer to plant sweet potatoes; learn about marketing, branding, social media, and direct sales; harvest the yield; and produce and package a product (sweet potato cookies). We’d sell the product throughout the year, then start the whole process again the following summer.

The Sweet Potato Project was but a teaser for a larger, more expansive vision — one that would involve low-income youth and Black adults being gifted vacant lots to grow food. I envisioned urban growers selling produce at new farmers’ markets close to home. With unrestrained imagination, I saw a government-funded processing and packaging plant where food grown in the ‘hood was converted into food-based products from the ‘hood (think Del Monte, Kraft, or Glory Foods). It would not only instigate self-pride in Black communities, but the grand vision would introduce a visible, viable, controllable mechanism that could generate wealth while teaching urban youth how to achieve real-life, sustainable careers outside the fantasy realms of sports, music, or entertainment.

My project ended in 2019.

Why? It wasn’t the youth. No, they easily grasped the concept, the lessons, the planting, harvesting, production, and packaging, and they dutifully sold their cookies.

It was me. My vision was much bigger than my skill. I was ill-prepared to raise the thousands and thousands of dollars needed every summer. I was a poor administrator; I lacked the know-how to recruit the right people to raise money or connect politicians, agricultural experts, or local restaurants and grocers to my idea. I needed that expertise to guarantee land, provide resources for large-scale farming, fund farmers’ markets, or help urban growers access a food collective (grocers, restaurants, and consumers) that would purchase the produce and products we made. In fairness to my own shortcomings, there seemed to be no system open to people like me with all those pertinent parts.

Financially busted and spiritually broken, I ended my program. The dream, the possibilities, however, still percolate in my soul. Ironically, after ending my nonprofit, I started to see promising progress in the local food environment.

Electric spurts of optimism have been sparked by news of emerging food-related endeavors. Millions in federal, state, and local funding have been directed to urban farming and community-driven food production, processing, and distribution. In 2022, the Biden-Harris administration announced it was doubling down on the federal government’s work to address hunger. The administration is committed to improving food access and affordability, integrating nutrition and health in its efforts. Locally, nonprofits committed to addressing food access in low-income urban communities have won grants from the state. A community grocery store with “healthy living programming” will open soon in North St. Louis County on property that had been vacant for more than 10 years. An almost $5 million urban agriculture education center is planned for the Shaw neighborhood of St. Louis.

In 2023, I was introduced to Food City from the Serving Our Communities Foundation. With promises to create “a more inclusive food ecosystem in the region,” Food City is supporting a wide range of food industry workers, consumers seeking access to fresh and healthy options, food entrepreneurs, farmers, youth, and others hoping to build careers in food.

Oh my! Can these promising efforts serve as a catalyst for an equitable and profitable food ecosystem in St. Louis? If so, how will the many, many challenges be met? According to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) data, 33% of the population — including those in urban and rural areas — live between one and 10 miles from the nearest supermarket, supercenter, or large grocery storeB1. In St. Louis, the majority Black areas north of Delmar Boulevard depend on fast-food restaurants, gas stations, or corner stores that serve unhealthy, sugar and fat-filled packaged or frozen food products.

In other words, the generational cycle of food apartheid still exists, undoubtedly impacted by historic injustices, disinvestments, and poor policy choices.